Sparse Word Embeddings

In this post, I’ll give a brief introduction to word embeddings, how they’re trained, why sparsity is important and how we can induce it.

What are word embeddings?

In the broadest sense, for a computer to learn anything about language, we need to represent words (sentences, paragraphs, text etc.) as numbers (a vector). A naive way to do this is one-hot encoding: take a vector that’s length is equal to the number of words in, say, the English language. Then each word will have its own dimension which we set to 1 when we want to represent it. A few things make this a poor way to represent words, such as the length of these vectors will be extremely large and increases algorithmic complexity exponentially. So NLP researchers turned to Deep Learning to learn better representations of words.

How do you train a set of word embeddings?

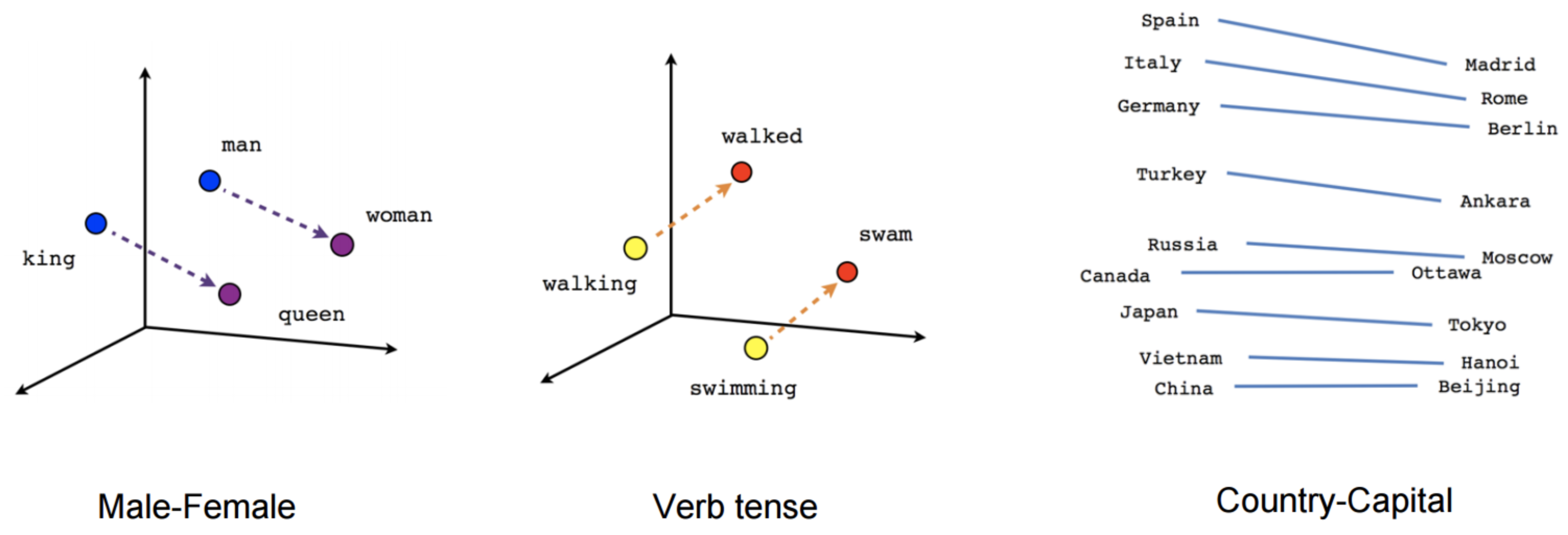

Word embedding models like Word2vec aim to encode semantic meaning of language by mapping words into low-dimensional dense vectors of real numbers through looking at a words context in a sentence in the hope that words with similar context occupy a similar region in the embedding space. They learn these representations by using large amounts of unannotated text to build a neural model that predicts word co-occurance. The hidden weights of this nerual network model are then used as dense word representations, which we call the word embeddings. The two main neural network archetectures used are Continuous-Bag-Of-Words and Skip-gram, for which there’s an abudance of great material online to help understand these (see Further Reading below.)

What is sparsity and why do we care about it?

Simply put, sparsity is the percentage of an array (vector, matrix, tensor etc.) that is zero.

Whilst successful and widely used, dense embeddings can had a few drawbacks: they weren’t computationally efficient and, more importantly, lacked human interpretability, they’re opaque. We don’t know what dimension in a word vector represents the gender of ‘man’ or ‘woman’. What does a ‘high’ or ‘low’ value in a particular dimension mean? So, we ask ourselves, can we improve the interpretability of Word2Vec type models while keeping their promising performances?

Sparsity offers a solution to this. We turn to psychology for motivation: in studies where participants are asked to list properities of words to describe a concept they typically usd few sparse characteristic properities to describe them, with limited overlap between difference words, also avoiding negatives. For example, to describe the city of New York, one might talk about the Statue of Liberty or Central Park, bt it would be redundant and inefficient ot list negative properties, like the absence of the Effiel Tower. Sparsity also has other benefits including lighter models and better computational efficiency.

How do you induce sparse word embeddings?

There are largely two categories for creating sparse word representations: i) inducing sparsiy online during embedding training using a regulariser, or ii) converting dense word vectors into sparse vectors through post-hop processing.

Regularisers

Regularisation in Machine Learning essentially boils down to adding a term to our loss function that induces a particular behaviour of our solution space. The most common regulariser is the $\ell_2$-norm, which takes the sum of square of each parameter of our solution.

\[Loss_{new}(W) = Loss_{old}(W) + \lambda \sum_i w_i^2\]It turns out that one norm exactly describes sparsity - the $\ell_0$-norm, defined as the number of non-zero elements of a vector. Sounds great, however such a function isn’t differentiable, meaning we can’t use backpropagation to train our parameters. One solution, porposed in this paper by Sun et al. is to use the $\ell_1$-norm as a differentiable approximation to the $\ell_0$-norm. A challenge of optimisation using this regulariser is that SGD fails not produce sparse solutions since the norm is not scale invariant; the solution presented uses Regularised Dual Averaging to address this issue.

Something I looked at as part of our final group NLP project this year, was using a novel regulariser to induce sparsity for which standard optimisation algorithms could be used: enter the Hoyer-Square regulariser: a scale-invariant, differentiable approximation to the $\ell_0$-norm defined as the ratio between the $\ell_1$-norm squared and the $\ell_2$-norm:

\[H_S(W) = \frac{\sum_i |w_i|^2}{\sum_i w_i^2}\]Our proof-of-concept method, using the Hoyer-Square regulariser on the skip Skip-gram model to train interpretable embeddings - check out our repo WAKU here. \(Loss_{new}(W) = Loss_{old}(W) + \lambda H_S(W)\)

Post-hoc processing

This is a somewhat more explored & practical category, since training high quality embeddings from scratch can be expensive (high quality $\implies$ large training corpus + even larger training time) so transforming readily available pre-trained embeddings into sparse & interpertable versions of themselves can be preffered. A couple of examples of such methods are one by Faruqui et al. that uses sparse coding & SPINE from Subramanian et al., which employs a denoising $k$-sparse autoencoder, trained to minimise a loss function whcih includes a reconstruction loss term and penalty terms for lock of sparsity.

There you have a very quick intro to sparse Word Embeddings. Check out Part 2 of this series where I’l talk about how to evaluate a set of word embeddings on their expressive power and interpretability.

Further reading

- Towards Data Science introduction to Sip-gram and CBOW models. For more detail, my favourite tutorial on the Skip-gram model

- Original papers for probably the two most famous embeddings Word2Vec and GloVe

- Gensim is a fantastic, fast, and easy-to-use library that implements the Word2Vec family of algorithms.