Recommender Systems: a brief introduction

Why?

The rapid advances of technology in the past decades have given us an abundance of choice. Anyone connected to the internet has access to a mass of information and a plethora of various types of content, more than can be consumed in a lifetime. Recommender systems try to improve customer experience through personalised recommendation for products or services, which suit and match their unique preferences. The algorithms behind those systems, such as Netflix or Spotify, profile users and items largely based on past interactions. The most extreme example is probably TikTok, whose core product is its recommender system, that’s achieved success by any measure in capturing the attnetion of its customers across the world.

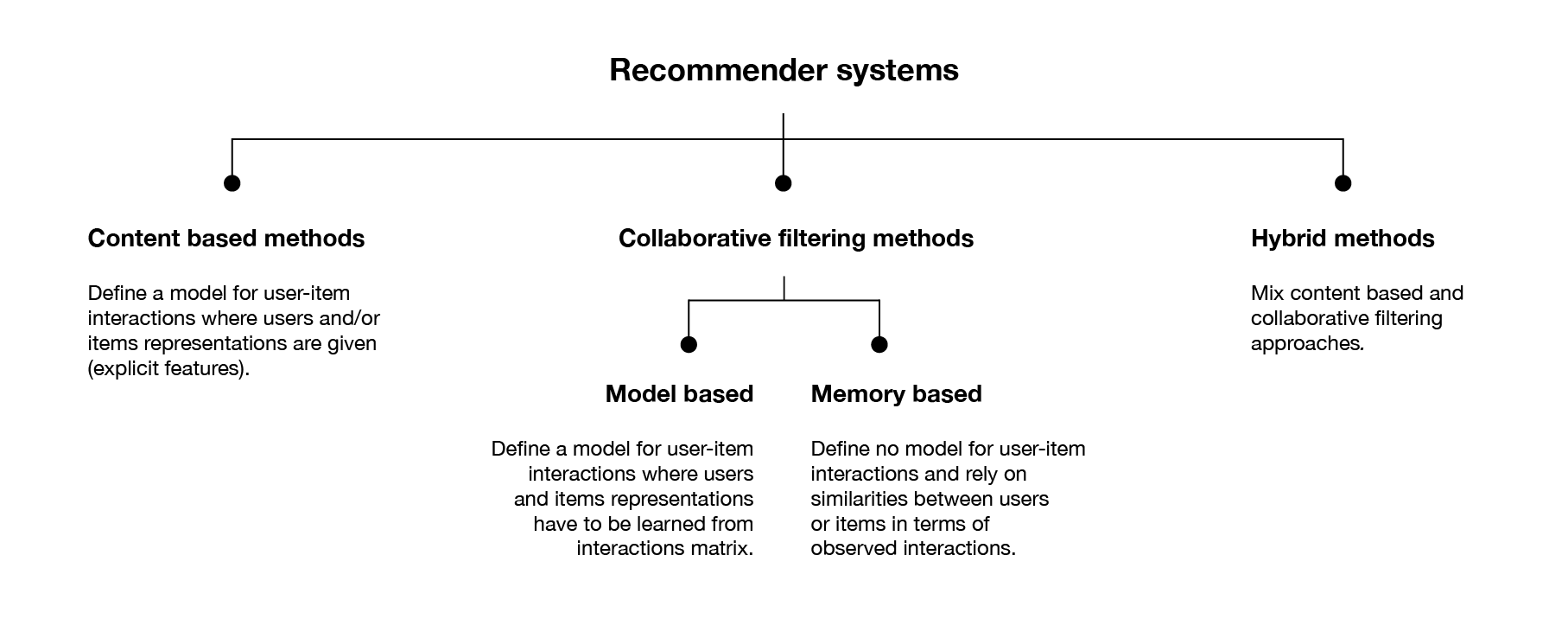

Recommender systems build a model to predict the relationship between fundamentally different objects: users and items. These models fall into three main paradigms: Collaborative filtering methods, Content based methods and Hybrid methods, which combine the two.

Collaborative Filtering

A term coined by the inventors of the very first recommender system Tapestry, Collaborative Filtering (CF) looks solely to past user behaviour - previous interactions or product ratings - to build a model of their preferences. They require no information about each user, nor any domain knowledge, thus avoid the need for extensive data collection and offer powerful prediction techniques with readily available information. As such, CF methods has gathered lots of attention in recent years, spurred by the famous Netflix Prize where the company released a dataset of 100 million movie ratings, challenging the research community to develop new methods to better the accuracy of its own recommendation system.

To make recommendations, CF algorithms fall into two approaches: neighbourhood (or memory based) approaches and latent factor (or model based) approaches. Neighbourhood approaches are based on computing the relationships between items, or alternatively between users, working directly with the recorded interactions. These were user-based in their original form where predictions for unobserved ratings or interactions were made using the preferences of similar, or like-minded users. Item-oriented approaches evaluate the preference of one user to an item based on their own ratings of similar items. These methods represent users as a basket of rated items, thus transforming them into item space allowing a direct comparison between items, instead of comparing users to items. However, all item-oriented approaches share the same drawback with respect to implicit feedback in that they cannot make a distinction between user preferences and the confidence in those preferences.

Latent factor models transform both users and items to the same latent factor space, thus making them directly comparable. We assume a latent underlying model from which interactions are drawn and from which new representations of users and items are built. A large class of CF algorithms fall into the category of matrix factorisation (MF) models whereby the interaction matrix is assumed to be well approximated by a low rank matrix. The latent factors can often correspond or be interpreted to be underlying features of the items, whilst the corresponding user factors relate to preference of those features - for example in music recommendation, these item factors may relate to the mood of a song, or its tempo. Many of these dimensions will of course be completely uninterpretable, left to the system to discover itself without no intuitive meaning. However, a consequence of such factorisation is that users with close preferences or items with similar features have close representations in the latent space.

Formally we can describe MF as follows, using the traditional indexing letters for distinguisihing between users and items: $u, v$ for users, $i, j$ for items and defining the following:

- $R = (r_{ui})_{N\times M}$: the user-item observation matrix e.g. movie ratings

- $\mathcal{O} = {r_{ui}\in R: r_{ui} \neq 0 }$: the set of observed interactions

- $x_u \in \mathbb{R}^f$: latent factor for user $u$

- $y_i \in \mathbb{R}^f$: latent factor for item $i$

Here, its important to note that $R$ is very often sparse, leading to many implications for both algorithm design and training. Generally we can frame the goal of a recommender system is to reproduce a dense $\tilde{R}$ from sparse training data $R$ that `fills in’ the missing user-item interactions.

Framed this way, a typical formulation of MF looks to factorise $R$ into the product of two smaller dense matrices, with predictions made by taking an inner product: $\hat{r}_{ui}=x_u^T y_i$. Learning is achieved by minimising the following loss function where $\ell_2$ regularisation terms have been added to avoid overfitting:

\[\mathcal{L}(R|X,Y) = \sum_{u,i \in \mathcal{O}} (r_{ui}-x_u^Ty_i)^2 + \lambda\big( \sum_u ||x_u||^2 + \sum_i ||y_i||^2\big)\]Content-based methods

Content-based methods use information about users and items to build a model that, based on these features, can predict unobserved interactions or ratings. For example, in movie recommendation, you could use users’ age and sex whilst also looking at movies’ length, main actors or genre to predict a rating. Armed with user or item information you can use a simple linear classifier or a model such as Naive Bayes as a recommender system with the goal of predicting a rating or binary interaction. While CF is generally more accurate than content-based approaches, it suffers from the cold start problem - its inability to address new items to the system, for which content-based models are adequate.

Implicit vs Explicit Feedback

Two types of data are generally available to build recommender systems: one includes the users’ explicit rating or score on items, the other corresponds to a count of the interactions between users and items (clicks, purchases, views, playcounts), referred to as implicit feedback. Often collecting enough explicit data for building a recmomendation system proves difficult, since users must actively provide feedback. In contrast, implicit feedback is rather easy to assemble - behaviour logs of most services are almost always collected. So its common to see recommender systems widely deployed in the implicit setting due to the practical availability of such feedback. As the world shifts further online, implicit feedback becomes more and more abundant.

What’s different about implicit feedback? As outlined in the seminal paper for implicit recommender systems, there’s a few special considerations that need to be made:

-

No negative feedback. By observing user interactions, we can probably infer which items they like - those they chose to consume. However, the same can’t be said for items a user did not like e.g. a user who doesn’t listen to a particular artist may just not have come across them before. This fundamental asymmetry does not exist in explicit feedback settings. As a consequence, explicit recommender systems can focus on the observed user-item pairs and omit the vast majority of `missing data’ from their models. This is not possible with implicit feedback, since only using positive observed data misrepresents user profiles entirely.

-

Implicit feedback is noisy. Even once user interactions have been tracked, the motivation behind a click, playcount or bet are still unknown: the item may have been purchased as a gift, or perhaps the user is disappointed with the artist. They may have just left music on shuffle or the television on timer, whilst the user is away from the screen. This adds uncertainty to the preference we can infer from observations.

-

Preference vs Confidence. The numerical value of explicit feedback represents preference (a star rating 1-5), whilst in the implicit setting feedback indicates confidence. A high count can be deceptive since, for example, frequency of events matters greatly. In the \textit{Kindred} dataset some events occur every week (e.g. Premier League) whilst some occur rarely (e.g. Elections). One-time events can occur by nature of the item, such as an Athletics meet that happens twice a year, however in general, a high count for a recurring event is more likely to reflect a positive user opinion.

Evaluation

The best, perhaps only true, evaluation of a recommender system lies online in production, when users are presented with live recommendations and their reactions are tracked. Online evaluation may involve A/B-testing or multivariate testing to tune a model based on metrics such as click-through rates or conversation rates. However, in the absence of such processes, as is often the case in academic research, there exist several metrics that recommender systems can be optimised for depending on the formulation of the task and form of feedback available.

For offline evaluation with explicit feedback the task of rating prediction is most common, where a model aims to predict the (often discrete) rating given by a user to an item. Of the observed ratings, a portion are held back to form a test set whereby predicted ratings are then evaluated using metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE) or root mean squared error (RMSE), as in the Netflix Prize.

In the implicit feedback setting, two tasks are commonplace: top-$n$ recommendation and pure ranking. For both, the model outputs a list of items, ordered by how likely the particular user is to interact with each item. In top-$n$ recommendation this list is truncated and we seek to evaluate the accuracy of the top results returned, a common task appropriate for implicit feedback datasets . These are most often evaluated using information retrieval metrics, such as precision (Pre@$n$), mean average precision (MAP@$n$) and truncated normalised discounted cumulative gain (NDCG@$n$). The ranked lists are assessed against the ground-truth, which consist of items the user actually interacted with in the test period. The primary metric for evaluating a full ranked list of items is mean percentile ranking (MPR), which has the advantage of assessing the whole output not just the top-$n$ recommendations.

Finally, we bring attention to this paper that finds the research community faces a challenge due to a lack of standardisation in the numerical evaluation of baselines. The paper demonstrates the issue on two extensively researched datasets by improving upon the reported results of newly proposed methods with careful setup of a vanilla matrix factorisation baseline.

There you have a very quick intro of recommender systems, the topic of my MSc thesis. Check in soon for most posts on the model I developed.

Further reading

- A more thorough and very good introduction on Towards Data Science.

- Great blog post on evaluating recommender systems

- Detailed list of online recommender system code repositories. Also my favourite repo for implicit recommender systems.